The 1989 El Salvador FMLN Guerrilla Offensive: Part IV: - “Death from Above” to the Truce at the Sheraton.

Tuesday, November 21, 1989

Ten days into the FMLN guerrilla offensive, chaos reigned in San Salvador, the capital of El Salvador. Few anticipated that the offensive would last this long. The US-backed government maintained control of the airspace. It used it to attack the insurgents while also terrorizing the civilian population, most of whom resided in impoverished neighborhoods and shantytowns. The fragile houses in these areas, with their corrugated aluminum roofs, were easily penetrated by even simple rifle fire, providing no protection from the "death from above" delivered by planes and helicopters equipped with miniguns, rockets, and 500-pound bombs.

Any inhabitant of any barrio who had witnessed their neighbors being killed by a Salvadoran government airborne attack would think twice about “sheltering in place.” After such an attack, they would likely gather what was left of their families - and, under cover of hastily made white flags held aloft, flee to safety – somewhere – anywhere.

As a result, the strategy of the FMLN had to evolve or fizzle out. El Choco, a mid-level rebel commander, explained that the decision to withdraw from the poorer neighborhoods was intentional. He stated, “We are in the affluent neighborhood of Escalón today to see if the Air Force will do here what they did to the people when they bombed the poorer areas.”

The guerrillas were now moving into the wealthier parts of the city, particularly in the Escalón and San Benito neighborhoods, which extend across the hills and ravines leading up to the San Salvador volcano. Since the upper class, allied with the military, owned these expensive properties, air attacks would likely be severely restricted. Even if such attacks did occur, the homes of the wealthy were constructed much more sturdily and more resistant to attack.

In addition, residents of the wealthier neighborhoods typically employed maids—sometimes several in a single household. These maids most often came from poorer backgrounds and frequently sympathized with, or even supported, the guerrillas, who were often their relatives.

Another benefit emerged from this situation. When guerrillas occupied properties owned by upper-class residents, it often led to conversations between the captured individuals and the guerrillas, who now shared a common enemy: the Armed Forces (ESAF), which, even if it didn’t bomb, was always threatening to do so. This scenario began to foster a shift in mentality amongst the wealthier classes, one that started to seek a peaceful resolution.

Into this turbulent scene entered a Brazilian diplomat based in Washington, DC. The white-haired and dignified-looking OAS Secretary General Joao Baena Soares had come to El Salvador hoping to arrange a ceasefire. He and his entourage had been staying at the main building of the Sheraton Hotel in the Escalón District. Perhaps unbeknownst at first to the visitors, Escalón was now also the temporary home of many members of various FMLN organizations—now hiding out in residential houses and often controlling whole blocks near the hotel.

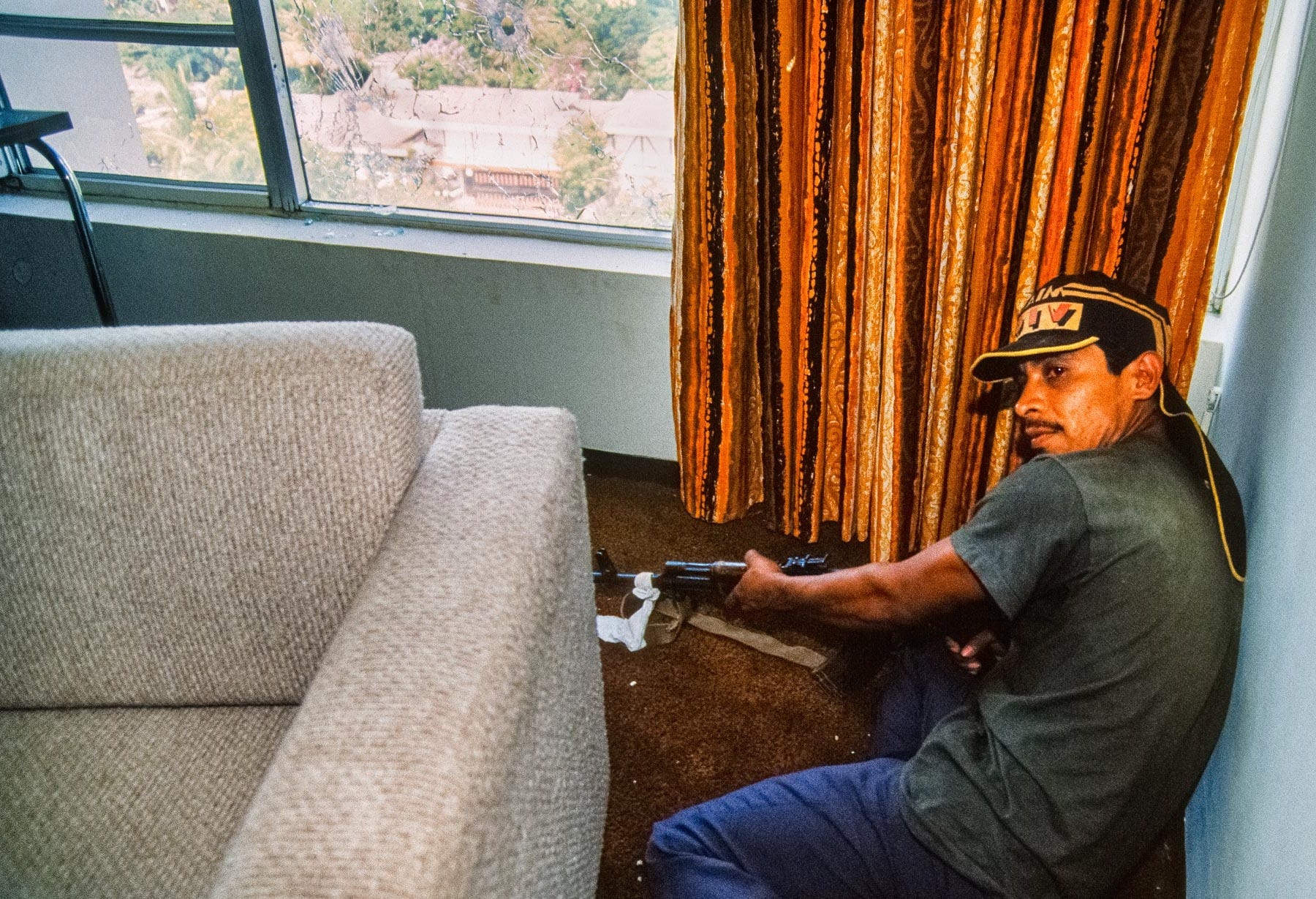

Just a few hundred feet from the main Sheraton hotel, where Baena Soares was staying, there was a smaller, more isolated six-story building known as the "VIP Tower Annex." The upper floors of this building provided a sweeping view of the surrounding area. In any conflict, controlling elevated positions is crucial, and this made it an ideal location to station a platoon of FMLN guerrillas equipped with at least one Dragunov sniper rifle.

A guerrilla platoon led by "El Choco" took control of the VIP Tower Annex before dawn, following several firefights outside. Unbeknownst to the guerrillas, who lacked a guest list, many Americans and foreign nationals were staying in the building.

The group of paying guests included at least one official from the U.S. Embassy and his wife, a journalist, several unarmed military advisors, and various intelligence agents from the U.S. and other countries, including Israel (this will be the subject of another story). On the fourth floor, there was a contingent of U.S. military officers from a Mobile Training Team (MTT) who had engaged the rebels without causing any casualties. After that, these American advisors had hunkered down in their rooms – with guerrillas above and below them. According to Radio Venceremos, there were four U.S. members of the MTT, one from Guatemala and another from Pinochet's Chile. Radio Venceremos added that the guerrillas were respecting their safety - and, apparently, their privacy also.

The presence of U.S. government officials, American and foreign troops, and civilians from various countries in the FMLN-dominated VIP Annex placed the U.S. government in a challenging position. Any military assault, even by well-trained commandos, would likely result in "collateral damage" and possibly the deaths of innocent people, including Americans. All US officials could do was complain to the press. White House spokesperson Margaret Tutwiler whined, “Sending 100 to 150 guerrillas into a Sheraton where civilians and private citizens reside is certainly not civilized behavior.” However, the actual number of guerrillas was closer to fifteen, not the 150 that Tutwiler claimed.

Although Baena Soares had not been in any real danger from the guerrillas, the Salvadoran Army dispatched its best troops to “rescue” him from the main part of the hotel. "Thanks to the quick actions of the glorious Armed Forces, the OAS Secretary General is now under the protection of a special unit," stated the official voice on my portable NiCad battery-powered radio. Later, it declared, "The glorious Armed Forces have thwarted a terrorist attempt to kidnap the OAS Secretary General in this capital." However, there had been no actual kidnapping attempt.

Throughout the day, the few hundred feet between the main building of the Sheraton Hotel and the VIP Annex was considered no man's land. The Army had deployed snipers in a semicircle around it, and guerrillas above could easily see it.

As the dawn curfew was lifted, news of the situation at the Sheraton quickly spread throughout the press corps. Soon, the entire media presence in El Salvador and their drivers and fixers gathered at the Sheraton. I drove there with Joni, the Salvadoran fixer for a Dutch TV channel. At times, it felt like there were more journalists than combatants, with nearly everyone congregating on the main streets outside the hotel.

Fortunately, there was plenty to photograph. The Army provided an entertaining show, a specialty of theirs. Salvadoran homemade tanks—known as "tanquetas"—cautiously roamed those nearby streets that were considered relatively safe.1 At the same time, soldiers dashed back and forth across these streets as if they were under heavy fire. In short, it was a great day for capturing photos and videos of "action," even if much of it was staged.

A Hughes 500 helicopter, armed with a minigun, approached the FMLN-occupied VIP Annex tower, seemingly aiming to target the top floor. A single shot pierced the hum of its rotors, and a stream of smoke erupted from the aircraft's tail. The helicopter shuddered, awkwardly looped around, and made its way back to an unseen landing, likely an uncomfortable one.

As Joni and I stood among the crowd of journalists outside the Sheraton’s main building, I noticed a man who appeared to be an American, likely in his forties or fifties. I hadn’t seen him before. He seemed to be intently observing his surroundings, noticing details that someone familiar with combat would pay attention to. I told Joni to keep an eye on him. Clearly, he was involved in intelligence work, but his demeanor suggested he was not necessarily hostile.

As the morning turned into afternoon, members of Baena Suares’ entourage and various prominent figures came and went from the Sheraton, always under the watch of a military presence. However, the more significant events were the unescorted delegations led by now-Cardinal Rosa Chávez, the head of El Salvador’s Catholic Church. He traveled alongside two other foreign church leaders, and their demeanor suggested hope for a peaceful resolution. It was clear that serious negotiations were underway.

It was now mid-afternoon, and the curfew was set for 1800 hours. We needed to be off the streets by then. I needed to take a pee. The VIP Annex was only a few yards away from the main hotel, and there were bathrooms inside. But there was the tricky issue of the perhaps 100 ft of no man’s land between us and the VIP Annex.

I couldn't see any soldiers or guerrillas at the edge of no man's land. Joni was behind me, followed by fifteen or twenty journalists. We decided to run for it. With our hands held high, Joni and I quickly crossed into no man's land, and a dozen or so journalists trailed behind us. I made my way down the path to the door. When I looked back, I noticed that some of the journalists who had followed us had turned back.

Having heard that Americans were on the fourth floor, I charged up the stairs. Turning to the right, I looked down the hallway and saw a man pointing a Colt .45 caliber pistol at me, something that, after several years in El Salvador, seemed quite unsurprising. I realized that the others behind me were no longer following me. Hands high, I kept walking toward the 30-year-old-looking young American soldier, who said, “One more step, and I will blow your brains out!” I said, “Be calm,” I retorted, “I was merely looking for the bathroom.” He gave me a surprised look. Before the conversation could continue, I quickly turned around and left. The others who had remained in the stairwell behind me shouted, “Press! - don’t shoot!” as they moved up the stairs to the landing. Once on the landing, journalists yelled questions down the hall at the US MTT advisors, one of whom was fluent in Spanish. He kept repeating, “We are from THE EMBASSY.’” Everyone knew EXACTLY which embassy they were from.

Joni had caught up with me, and the American spook was right behind her. We made it up to the fifth floor, where two guerrillas armed with AKMs watched for the enemy through a stairway window. They signaled us to keep going upstairs. A handful of other journalists followed us.

There, on the top floor, a very attractive blonde hotel guest was lying on the carpet – smiling as we passed her. I came back for a couple of photos. On the floor were the “papayas” – the grenades to be twisted onto the propellant sticks of an RPG, their safety pins untouched. One rolled as I passed it, and a woman journalist behind me recoiled in shock. The American spook told her that everything was OK in broken Spanish. “Papayas” can’t explode until you remove the safety pin.

I entered a guest room and saw an FMLN combatant who I had met before armed with a Dragunov. I took a few pictures and asked if I could use the bathroom. He agreed but asked me not to close the door. Feeling relieved, I returned to the hallway and photographed several FMLN combatants and hotel guests. The bullet holes in the glass windows were spectacular in real life but didn’t make for good photos.

A journalist coming up the stairs informed us that we were now in a “one-hour ceasefire truce” and that the curfew had been extended by ten minutes, lasting until 6:10 PM. He said we should leave soon so everyone could get home before curfew. He also indicated that there was a problem downstairs.

The US MTT “advisors” had kidnapped a group of journalists and were holding them face-down on the floor as human shields downstairs. I thought of these advisors and how scared they must have been. No one could have trained them for this. For years, I had intercepted their communications over my scanner and taken notes when they talked about going into and out of “Indian country.” Now, the “Indians” had come to them.

It was 1745 hours, and the press and guests had begun to leave the top floor. Joni and I followed them, but we were slowed down by the massive crowd of journalists released by the US MTT advisors. Everyone was anxious while crossing no man's land, but there was no reason to be. Rosa Chávez’s cease-fire was holding.

As they left, VIP Annex guests were ushered into a convoy of the waiting ambulances of the Red Cross, as well as other Salvadoran entities that performed similar functions. This was all done like clockwork. And it had to be. It was already getting dark, and with the curfew coming up at 1810 hrs, there was no time to spare.

The guerrillas quietly slipped out as darkness fell, moving into the rivulets that ran up and down the volcanic slopes.

The U.S. MTT "advisors" – the ones who had pointed a Colt .45 at me and had forced more than a dozen journalists face-down on the floor - chose to stay overnight at the hotel by themselves. Without room service.

On the street outside the Sheraton, the American spook asked if we could give him a ride to the Camino Real Hotel. I agreed, and Joni climbed into the back seat while I started chatting with our new acquaintance. I didn’t ask which agency he worked for, but I did share my observations about the indiscriminate bombing of civilian neighborhoods. I explained that the real issue in El Salvador was the ESAF - the Army, Air Force, and security state, which we, from the United States, supported.

By 1800 hours, we arrived at the Camino Real Hotel. As the American spook exited the car, one of the journalists I had seen in the VIP Annex's top floor rushed over and remarked, “You know, that guy looks like a spook.” I replied, “It doesn’t matter; the cease-fire was successful, and no shots were fired.”

Who was the “American spook?” And was he really an American? It is one of those questions that can nag you for years.

We had just nine minutes to get back from the Camino Real home. Fortunately, we made it with only seconds to spare. Joni chose to take her sweet time getting out of the car, leaving me holding my breath. Besides being reminded by soldiers outside the Sheraton, soldiers in the next-door IPSFA building had threatened to shoot us if we were caught out after curfew. To my relief, she managed to get inside by 1811 hours. A minute late. Once again, no shots were fired, and I could finally breathe again—at least a few breaths. Another chapter was about to begin.

The Spanish version of this article, translated by Guiseppe Dezza, can be found at ESPACIO Revista Digital.

El Salvador had to manufacture its own “tanquetas” (armored personnel carriers) because other countries refused to sell theirs because of its abysmal human rights record.