The 1989 El Salvador FMLN Guerrilla Offensive: Part II – Isabel and the Fight for Santa Marta

Co-published in Spanish in the Salvadoran publication ESPACIO Revista digital https://www.espaciorevista.com/memoria-bigwood-periodistas-en-la-ofensiva-guerrillera-de-el-salvador-de-1989-segunda-parte

November 13, 1989. I was home at 55 Avenida Norte, listening to the chatter from the scanner and the radio. The phone rang. I had been expecting it. It was Jennifer Coley, my boss at Gamma-Liaison, my photo agency. She told me she had arranged for me to work for the American magazine Newsweek this week. That was the good news.

The bad news was that the competition was also coming to town. The “parachuting journalists” from around the planet were now descending on San Salvador.

Hotels throughout the city were filling up, especially the luxurious (at least for El Salvador) Hotel Camino Real (now Real InterContinental Hotel) with its pool and bar, which in more normal times housed the wire services, the New York Times, The Washington Post, and The LA Times, and human rights organizations on its second floor. As the guerrilla offensive increased, the hotel became home to Salvador-based foreign journalists and aid workers fearing the fighting in the neighborhoods.

Dropping in on top of all of this was the well-coddled “Managua gaggle,” the journalists who lived in Nicaragua’s sultry capital. Those of us living in El Salvador considered ourselves a species apart – Managua was poor but peaceful – the US-backed Contra “counterrevolutionaries” were far away from the capital. They never got close. But living in El Salvador, the war was ever-present: the capital city was full of the US-backed Armed forces, death squads, and insurgent urban guerrillas. That didn’t mean that Managua was an entirely safe place. Partying, drunken journalists made driving at night extremely risky, and there were unabated epidemics of STIs furtively and nocturnally spreading through the community.

My boss also told me that arriving photographers working for mainstream news media were being given assignments to embed with the Salvadoran military. To avoid redundancy, I should bias my coverage to get more photos of the FMLN guerrillas if possible. And she reminded me - be safe! Gamma had already lost one American photographer, the well-regarded John Hoagland, in combat in El Salvador. She didn’t want to lose another. Neither did I.

With NiCad batteries fully charged, it was time to grab some film and hit the road. This time, I would only carry two cameras: one for my wide-angle zoom with ASA 100 Ektachrome and another for my telephoto zoom with ASA 400. Flash desirability was debatable, but I brought one along just in case.

Frank Smyth, the CBS journalist who lived in the apartment above me, invited me to accompany him to Santa Marta, a barrio in the south of the capital city, where he knew people in a Christian Base Community. At the time, there was a robust Liberation Theology movement in El Salvador—something that permeated and gave fighting spirit to the insurgency, especially since its leader, Monsignor Romero, had been murdered by a military death squad.

My car was still stuck in no-man’s land in Zacamil, so we drove to Santa Marta in Frank’s jeep. There was no time to worry about it now. If it was destroyed, it was gone—"y punto”—period, full stop. Now, I had better get some more decent images.

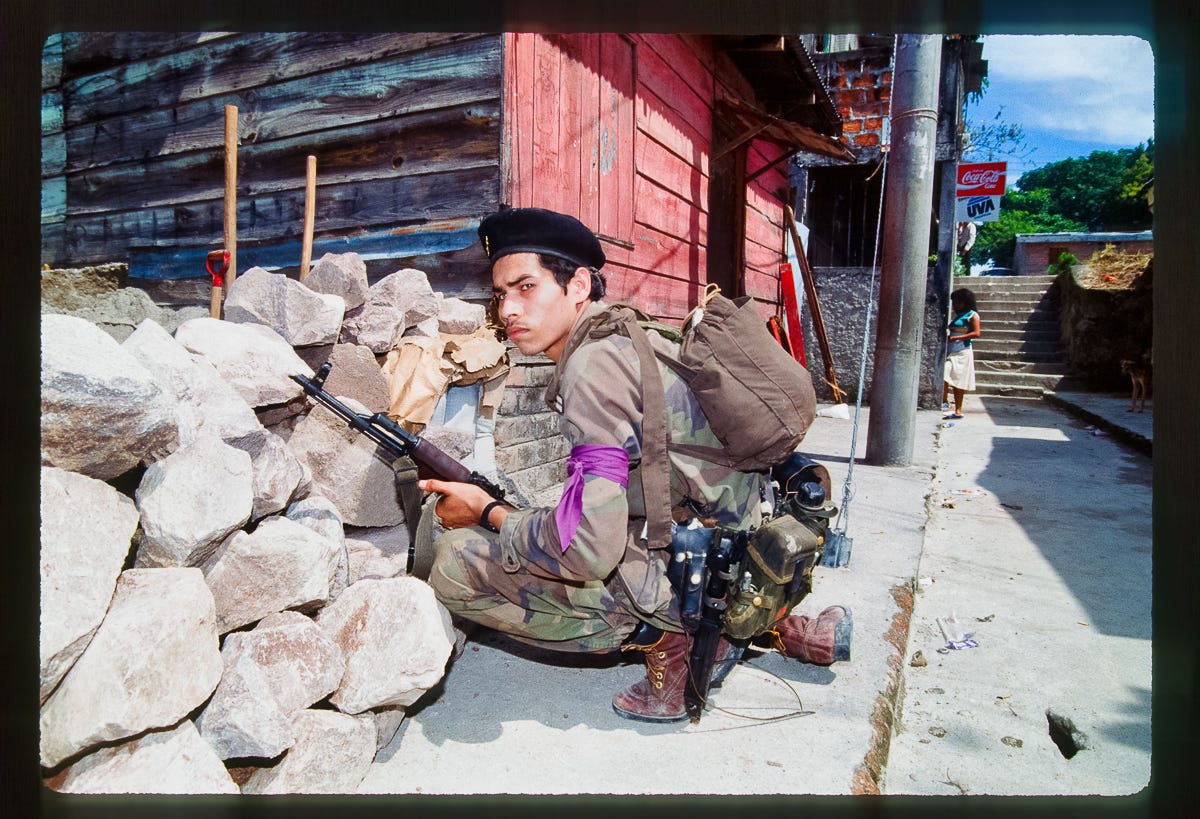

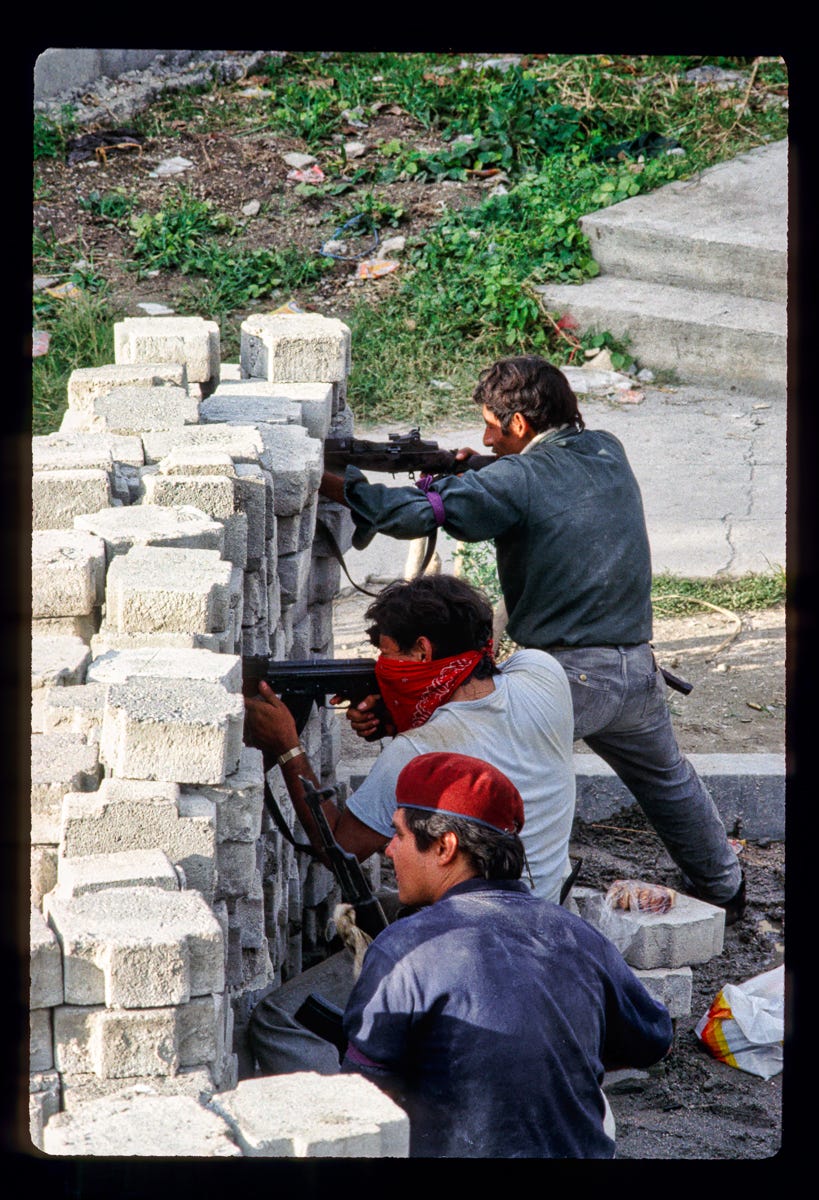

We parked on a hill. Because Frank had known people in the community, he knew exactly where to go. A quick trip on foot up a few streets, and we were in FMLN territory. After showing our official COPREFA and SPECA ID badges and identifying ourselves as journalists, the well-armed guerrillas waved us on. We passed by shoulder-high barricades made by digging up the bricks in the road. As we passed, I thought these would surely stop rifle fire but be utterly ineffective against anything larger, such as the bursts from a gunship’s miniguns or its rockets.

Walking up a hill, we came upon a newly built, almost gated, planned community addition on the city's southern edge. Few of the houses seemed occupied. Compared to most people's homes, these seemed expensive and not the kind of buildings the military would want to destroy. Why not? Because the people who constructed these must have had powerful connections. The Salvadoran security state danced to two main tunes – that of El Salvador’s super-rich oligarchy and, even more importantly, that of the United States government, which bankrolled them. This was something the guerrillas understood and were clearly incorporating into their plans. Such places provided good cover because of the military’s reluctance to destroy them.

A young woman with thick, beautiful hair sporting a purple armband identified herself as “Isabel,” an FMLN political officer, and invited us into a bare, unoccupied two-story house. There, she sat cross-legged on the empty floor, Kalashnikov in her hand. When I reached for my camera, she raised her hand and said, “Wait,” removed the armband, and used it to cover her face. “Ahora si,” – she said – “now, yes”- I could take pictures. Isabel had been recently captured and tortured by the almost universally despised “Guardia de Hacienda”- the Treasury Police. Somehow, she had made it out alive.

Santa Marta was Isabel’s neighborhood. She explained that these were guerrillas from the RN, a part of the FMLN insurgency – the Resistencia Nacional – or the “Renatos” as they were commonly known. Their roots in this neighborhood went back more than a decade. Frank took notes as I affixed my flash and photographed her expressive hands. After the interview, she walked us around to various positions in the area under their control – pointing me out to the combatants as someone who was allowed to take pictures.

There was a lull in the fighting, and Frank took this opportunity to retrace his steps home so that he could file.1 The Army and National Police had tried to push these guerrillas out of the area earlier but had failed a few hours before. Right now, the Army was laying down “probing fire” from their positions to the north, trying to determine where the guerrillas’ weaknesses lay. I took advantage of that to photograph the defensive positions behind the barricades. I offered bandannas to cover the faces of those who wanted them. Most didn’t take them.

On one street, I came across a series of bodies in front of houses, the exterior walls peppered with machine-gun fire. A distraught young woman with a loyal puppy dog, whose boyfriend was dead on the street, searched his body to remove anything that might identify him as having lived in her house. Weeping hysterically, she removed the burlap bag over him and rolled his limp body over to extract his wallet and ID. Now, if the security forces came and searched him, they would have no way of tying his remains to her. Her face in agony and tears streaming, she kissed and covered the body, and then she disappeared.

Just then, a renewed Army assault began, and I retreated to a safer area, where I met up with Isabel again. She assigned a young, wounded guerrilla to accompany me. He had been shot in the arm but could still fight. We spent some time in the makeshift infirmary on the first floor of a new house while he was getting his wound cleaned. There were several “near misses” amongst the wounded. Women guerrilla “brigadistas”- nurses - were working overtime.

The guerrillas had captured some soldiers on leave, and they were put to work digging trenches. This was a violation of the laws of war. Prisoners are not supposed to be put to work. But this “war crime” seemed minimal compared to what I had seen in Zacamil the day before.

My wounded guerrilla guide took me to one of the highest buildings in this planned community. On the top floor was a room with a clear neighborhood view. Guerrilla snipers fired through the windows. I snapped photos while the deafening sound of shots fired inside an unmuffled concrete room numbed me to the core. I felt like a human tuning fork.

The Army was trying to move up a street in front of me. Three guerrillas fought from a barricade, two with Kalashnikovs and one with an M14 rifle, probably taken during a guerrilla attack south of the city I had covered a couple of years before. After successfully repelling the assault, the guerrillas posed for a picture.

It was quiet again, and the sun was fading. My guide and I made the rounds of some of the defensive positions. Would the Army attack at night? No-one knew. I learned there was now an Army presence in the area Frank had exited through, so this was not the time to leave. In any case, the 6 PM curfew announced by the government was coming into play. That meant probable instant death if the Army or police saw me on the street. I realized I had to stay here and concluded that using my flash after dark was too dangerous, so there would be no more pictures until dawn.

Isabel offered to let me stay in a recently fixed-up apartment. There were two new white sofas against the wall and a bed with a bare mattress. I was to sleep here while Isabel, draped on a couch, aimed her Kalashnikov through a hole she had made in the wall. I had already snapped a picture of her in this position when it was light outside. It was too dark to take one now.

I fell into a deep sleep with the angelic figure of Isabel guarding over me. Yes, there were firefights throughout the city, but it was soothingly quiet here.

November 14, 1989, Isabel woke me an hour before sunrise. Had she been able to sleep? I didn’t know. Some “urbanos” - urban guerrillas - were just now getting ready to probe the exterior lines of defense. Did I want to come along? I popped a 200mg caffeine pill and joined the group, skittishly crossing open areas. The Army had retreated quite far overnight. They would be back. It was time to leave, cross lines, and get my film to my photo agency.

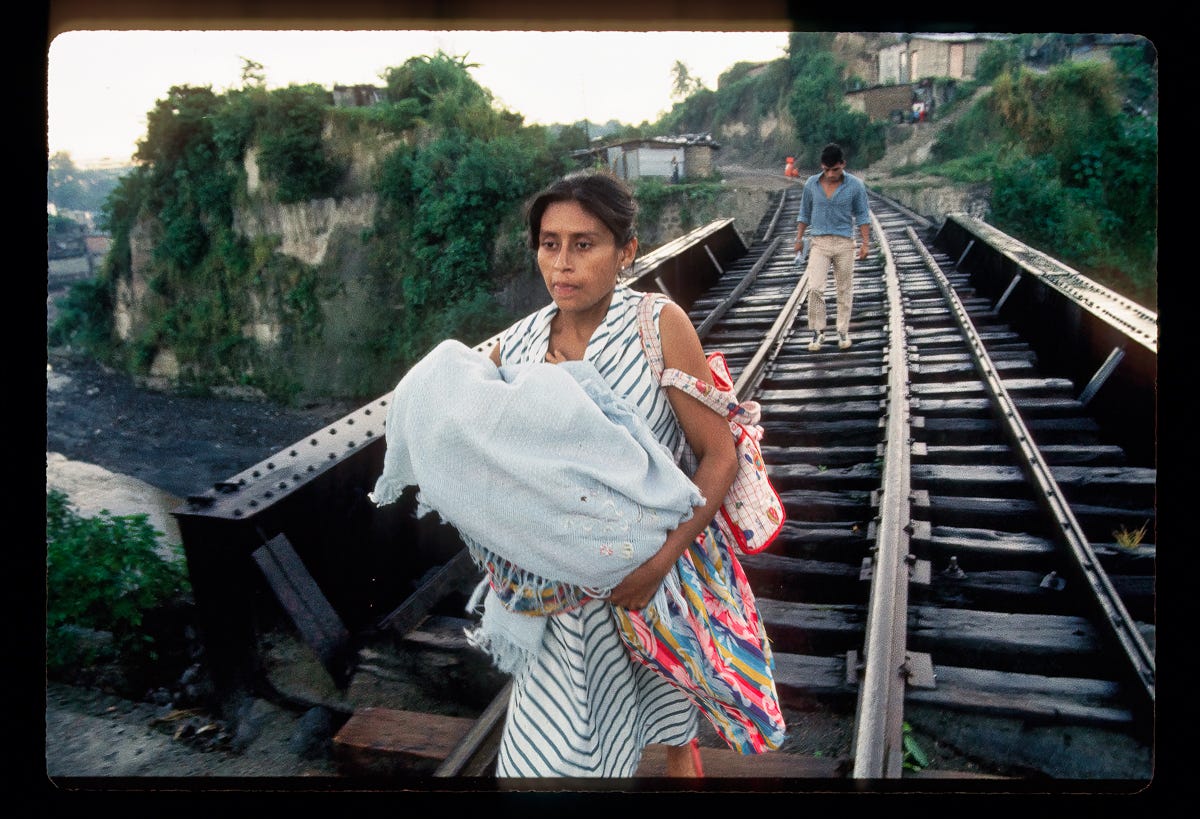

Just then, a door to a house opened, and a woman appeared. She was holding what seemed like a bundle of clothes in her arms. “I need your help to get to the hospital. My baby has been wounded,” she said without showing me her child. “OK. But we need to go out this way!” I retorted, pointing in a different direction than she was walking in. I had heard that the way Frank and I arrived yesterday was now free of Army positions. “My daughter is injured and bleeding,” she continued, “I need to get out of here as fast as possible. We need to use the railroad track – the fastest way out. Don’t worry; if soldiers are on the other side, they will let us through! Please!” The guerrillas around us were unsure of what the safest route was. From here, most of the tracks did look free. My gut feeling was that I did NOT want to go out this way. But someone’s life was in danger. These are the small, silly decisions that can save a life or get you killed. Very reluctantly, I agreed.

We started walking – me with my hands up – onto a crude railroad bridge over an almost dry rivulet. I was ahead a few steps and turned once to get a photo of the mother holding her child. Then I kept walking. A small concrete hut was ahead alongside the railroad, and I could see M16s pointed directly at us from inside. That made every step its own little nightmare. Don’t dare stop or stall! Make it all the friggin’ way to that concrete railway hut.

When I got near the hut, a hidden soldier started to yell at me. He accused me of being the American who had insulted a certain lieutenant - and that I was going to pay for it. Confused, there was nothing to do but keep walking. “Move him inside,” someone barked. I was pulled inside, and a sleepless, rabid-looking soldier shoved me up against the wall with his muzzle next to my head. “Don’t do it there!” shouted another soldier. “Don’t do it against the wall! Move him to the window. Your shots will ricochet all over this place!” Just then, out of the corner of my eye, I could see and hear the woman start to scream louder than I thought humanly possible. She was on her knees in the middle of the railroad tracks in front of a bloody mess of rags. “My baby,” she yelled as she flapped her arms. “My baby is dead! See what you have done.”2

The soldier who had been just about to shoot me turned around, and I thought I saw tears in his eyes. Like magic, a sergeant or an officer appeared, ordering everyone to get the woman off the railroad tracks. Turning to me, he said something to this effect: “You must be the American who insulted Lieutenant so and so. You are very lucky to be alive. You are going to the National Police.” I was dumbfounded but happy not to be shot - trying to figure out when and where I had insulted an officer. I said: “It must have been another American journalist. There are many here now!” “Liar,” he said. He cut some cloth off a poncho and blindfolded me with a piece of it. I could still see my feet but little else. Then he wrapped more of it around my arms and ordered two people (who I couldn’t see) to walk me a few blocks away.

Strangely, now I thought there was a good chance of this ending well. I still had my camera bag over my shoulder and what I knew were extremely good photos. No one had even bothered to look at my cameras – let alone remove the film. We got into a waiting Jeep Cherokee station wagon – the kind long associated with death squads. The blindfold was starting to come off, and I could see almost everything in front of me. The two cops accompanying me seemed upbeat to be away from the front lines. One told me that they hadn’t heard what I was accused of, but the head of the National Police had asked for me. We drove into a secure parking lot. As they helped me out of the car, my blindfold fell off completely, and the two cops just left it on the ground. They released the other part that had been binding my wrists. We walked past one of El Salvador’s rare policewomen. Seeing me pass, she dragged her finger across her throat. I rolled my eyes and gave her a look like she was nuts.

We walked into what seemed like a large building. Without stopping at a guard, we walked directly up some stairs into the office of the high official, and they motioned for me to enter while they stayed at the door. I didn’t recognize the official – but he wasn’t the boss. He looked tired but looked up from his desk and said, “Jeremías Bigwood – you shouldn’t insult our officers!” For me, that he knew my name was not a big surprise – all of the journalists who attended press conferences were filmed by state media. And the security forces kept tabs on all of us. Without hesitation, I answered that I hadn’t insulted anyone and that Salvadorans had often held that “all Chele’s (gringos) look alike.” He retorted something like, “Of course you would say that! Be more respectful next time! Do NOT insult our officers, especially in front of their men. You are free to go.” Whew! I was extremely fortunate it was this guy. Some officers in the National Police had a very nasty reputation. I couldn’t believe that I was now free. Now, I needed to find some transportation home. Luckily, there were still taxis on the street. As I traveled home, I wondered to myself if those soldiers along the train line were really going to kill me, or was this a classic “mock execution?” And why was I accused of insulting an officer? But there was no time for pondering such things. The offensive was now a major news story. I knew I had very good images and needed to get them to my photo agency.

It was still morning, and I needed my car! I called my Salvadoran friend, fixer Joni Chevez, who lived near Zacamil in the northern part of the city. Joni said I could find a cab on “la Roosevelt” and make it to her house. From her house, I could walk down the hill into Zacamil. I found a taxi and got there quickly, following her directions.

My car was just a few blocks away. This neighborhood had an eerie silence – but fighting was raging in other parts of the city. To get to my car, I had to walk by the Zacamil apartment building where I had photographed the aerial assault on the shantytown just two days before. As I passed, a guerrilla I had known from the countryside stood up on a balcony and waved to me. I wanted to go to him and ask him what had happened, especially to Marta, the guerrilla with the M16 I photographed a couple of days ago. But I needed my car, and I was sure it wasn’t only guerrillas watching me walk down the street. I walked forward slowly and deliberately – hoping that I exuded calm confidence, taking a deep breath with every step. Rounding a corner, I saw my grey car. It was intact. And it was on a slight incline.

Several blocks away, down this same street, was a military checkpoint where they were “filtering” out refugees. Then, I noticed a guerrilla with a Dragunov trained on the filtration checkpoint. Averting my eyes to not draw attention to him, I looked at my car. I could see that the tires were fine. The tape displaying the letters “TV” was still visible on the front and rear windows and the roof. The white flag, now wilted and more than a little dirty was still hanging from the antenna. There was some glass from the passenger’s side back window on the back seat and floor, but other than a bit of shrapnel, it looked OK. Maybe, if I am lucky, it will start all by itself!

I got in, inserted the key, and turned it. No dice! It was on a slight hill, so I tried to start it by half-pushing and half-sitting. It turned over and almost started, but “almost” doesn’t cut it. I opened the door, got out, pushed and pushed, and finally had enough speed to get it rolling enough to jump in and start it. Phew! We are on! Now for the Army retén (checkpoint) and the trip home.

I pulled alongside the well-sandbagged checkpoint. Close up, I saw the holes in the bags from guerrilla bullets. Looking ahead, I could see lines of refugees who had recently come through here, and they were up ahead, going through a secondary filtration point up the road.

Hidden by rows of sandbags, a weird-looking bespectacled officer with a strange accent spoken through very crooked teeth ordered me to get out of the car. I did. He wouldn’t move an inch from the protective cover of the sandbags piled two deep. I, on the other hand, was fully exposed to the guerrilla sniper with the Dragunov up the street I had seen before. I wondered what my side looked like through that sniper’s sight. The officer who was interrogating me seemed to be hoping for me to get shot. He asked a series of lengthy, stupid questions, and he didn’t seem to be from this country or this war. Finally, some more refugees came behind me, and he had had enough, and he permitted me to continue to the next checkpoint – the filtration point. This was manned by overworked regular soldiers who just let me pass, and I pulled over in front of them, parked on an incline, came back to photograph the refugees, and then drove home.

Safely at home, I was filling out my notes describing which images went with which roll of film when Frank burst in to tell me that Isabel, the angelic presence who had protected me all the previous night, was now dead - and that he was worried that the soldiers had found his business card – which he had given to her during the interview the previous day. While I was stunned and saddened by this bad news, I felt I had to tell him about my arrest and almost execution. Frank admitted that it was he who had chewed out the officer - but was nonchalant about what it had caused me to go through – after all, I was still alive. And while I was angry at Frank, I realized that my ordeal was indeed trifling compared to the news of the death of Isabel – such an intelligent, caring, and lively person who could have contributed so much to her country and the world. But, although I still grieve about it now, 35 years later, there was no time to focus on it then. Now I had to get my damn film to the airport thirty minutes south of the city. Taca Rapidito downtown was closed.

This article was written to be published in Spanish (translated by Guiseppe Dezza) in ESPACIO Revista digital:

https://www.espaciorevista.com/memoria-bigwood-periodistas-en-la-ofensiva-guerrillera-de-el-salvador-de-1989-segunda-parte-29-11-2024/

Frank Smyth, Caught with Their Pants Down – Why U.S. Policy and Intelligence Failed in El Salvador. The Village Voice -December 5, 1989: https://franksmyth.com/the-village-voice/caught-with-their-pants-down-why-u-s-policy-and-intelligence-failed-in-salvador/

See Pedelty, Mark “War Stores: The Culture of Foreign Correspondents” Routledge, 1995, p.130, where this author is given the pseudonym “Paul,” and a slightly different version of these events is recorded. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.4324/9781003100287/war-stories-mark-pedelty

Excellent shots Jeremy, hardcore…

Thank you, Jeremy, for helping the rest of us to see, feel and hopefully understand the rest of our world a bit more realistically.